All Human Rights for All: a Political Agenda

Antonio Papisca

L’Intervento di Antonio Papisca alla settima Assemblea dell’Onu dei Popoli.

Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Sisters and Brothers,

the Interdepartmental Centre on Human Rights and the Rights of Peoples of the University of Padua has been glad to contribute to the thematic preparation of the 7th Assembly of the UN Peoples. I am delighted to convey to you the friendly greetings of my old University, one of the oldest in Europe.

The Human Rights Agenda is the answer to the crucial question: why politics and for what goals.

More and more human rights interpellate politics and policying, because people are more and more aware that human rights are what they entail in their realisation.

Usually, when we say human rights we advocate for guarantees, to be free from want, from fear, from power….yes, the very Law says that we should be free from…

But human rights, before being guarantees, are the human being as such, la personne humaine en tant que telle.

We do are the human rights, each and all members of the human family are equally human rights.

We do are the constitutional core of the world legal system and of whatever system.

When article 1 of the Universal Declaration proclaims “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood”, it says that there aree rights – not arrogances, not luxury, not superfluous things – which are inherent to the human being.

As International law, the DNA of which is in the first part of the United Nations Caharter and in the Universal Declaration, states that “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world” we can actually say, benefiting from law support, that human rights are our individual and collective life, then that our life should be free from war, free from extreme poverty, free from discrimination, free from pandemias, free from pollution, free from dictatorship, free from terrorisms, free from fundamentalisms, free from arms race, free from ‘market first of all’.

Court rulings are absolutely necessary and inalienable in case of violations.

But a sure course to respect human dignity, that is life, is to prevent violations through promotion and protection rather than sanctions.

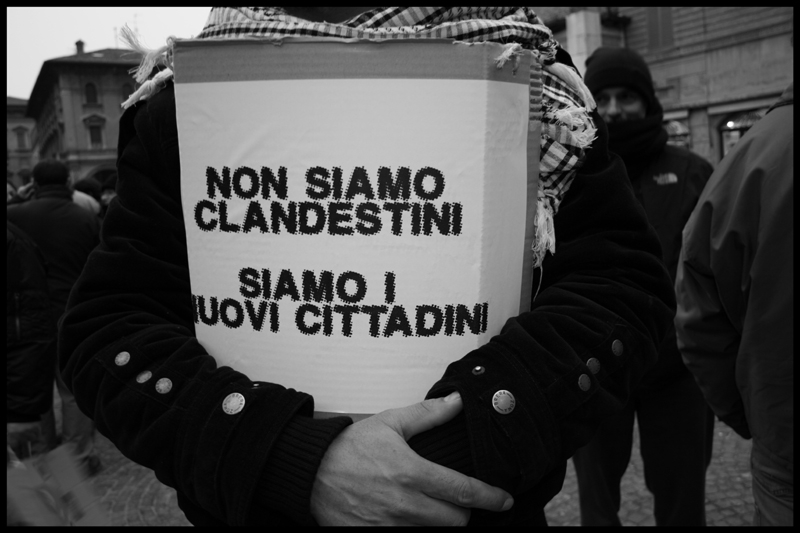

Human rights promotion means positive action, that in turn means policies, especially social policies to be endorsed and carried out at local, national and international level. What I am saying is that human rights are universal values and at the same time political goals for political decisions, then a specific political agenda is needed. As people endowed with universal citizenship, we reclaim human rights become a coherent and consistent political agenda: I mean each human right as the headline of a specific chapter of the political agenda.

It should be emphasised that the international legal recognition of human rights, started in 1945 with the UN Charter, has proven to be the greatest conquest of the 20th century that humanity has never achieved though at the same time that very century was afflicted by some of the bloodiest wars in history, by genocides, the holocaust, gulag, ethnic cleansing, the atomic bomb and environmental destructions. The International law of human rights, such as developed in the last sixty years, has triggered a human-centric revolution within whatever legal and political system. Needless to point out that such progress arose from centuries of claims, violations, human suffering, along a common path undertaken jointly by operators in the field of law and of social and economic justice.

On the eve of the 60th anniversary, the Universal Declaration and the whole International law of human rights need to be defended and developed with scrupulous respect for the basic principles of universality, equality, non discrimination, indissociability of women rights from human rights universally recognised. Let me insist on emphasising what I believe is a practical truth: human rights are what they entail in their concrete realisation. And no rebates are accepted on human rights, that is on life.

What I am stressing is that life, human rights and peace are inseparably intertwined and do not admit exceptions. Death penalty and war are acts of barbarisms and are incompatible with human rights: their prohibition has taken on a strong binding character, of ius cogens. Any infringement breaks the heart of legality and leads to perverse dynamics where the law of force prevails over the force of law, trapping into a spiral. Starvation, discrimination, extremy poverty are incompatible with human rights.

Il it necessary to point out that when we say life we refer to the integrity of the human being, made up of the body and soul, matter and spirit. Then the right to food, the right to health, the right to work, the right to education are no less fundamental than the right to freedom of association or the electoral rights.

The principle of interdependence and indivisibility of all human rights is transversal to any kind of prevention and protection of human rights. Consequently and in accordance with this principle, a consistent political agenda must provide equal space and weight to the guarantees of civil and political rights and to the guarantees of economic, social and cultural rights. Those who discriminate between civil and political rights on the one hand, and economic, social and cultural rights on the other, while fulfilling an arbitrary operation in terms of logic and from the juridical point of view, they directly attack human integrity. A genuine human rights political agenda must therefore be consistently inspired to a coherent vision in which the “rule of law” and “sustainable welfare state” are the two facets of the same coin.

Human rights are our vital needs that reclaim satisfaction in the daily life, in the city, in the village, in the farm, at school, at work. Their violations do happen at local level, where we live, while crucial decisions in both positive and negative directions are taken far from us. Wars are decided far from us, but bombs destroy our houses. Then in the era of complex planetary interdependence, of globalisation and profit and non-profit transnationalisation, a genuine human rights political agenda cannot but be “glocal”, to be built and carried on

at local, national, regional, international and world level.

We are aware that the world situation is not favourable to set up and realise such glocal political agenda.

As active members of the human family and as civil society representatives of the Peoples of the United Nations gathered in Perugia and Assisi, we strongly denounce that, despite the fact that the culture of human rights is spreading to, and through, organisations and transnational social movements, universities, schools, religious groups, local polities, the conduct of many governments, both inside their states and within the international organisations, proves to be oriented differently. Its baneful tendency being “more safety, less freedom” makes Realpolitik prevailing over the needs of peaceful and democratic development of societies. We can rightly speak of a governmental and intergovernmental shameful, even criminal misconduct.

We are fully legitimated to denounce the destructive effects of neo-liberism and de-regulation in both the economic and institutional field, the ongoing practice of torture, of illegal renditions, of traffiking in human beings, the tendency to weaken legitimate multilateral institutions, in primis the United Nations, preferring multilateralism and ‘multinational’ coalitions à la carte.

We denounce the persisting practice of obstructing the International Criminal Court.

We denounce the attempts of unscrupulous political leaders and governments to reclaim and put into practice the “rith to war” (ius ad bellum) that the UN Charter has, once and forll, deleted.

We denounce the extensive interpretation of article 51 of the UN Charter, that would give way to ‘preemptive’, ‘preventive’ and even ‘protective’ use of force by the states.

We denounce the attempts to export democracy through bombing. We denounce the criminal attempts to transform an ‘exception’ into a ‘general rule’: what is being prepared is a nightmare scenario of easy war.

We warn against the “call of the wild” that many governments are sensible to in order to relaunch the inauspicious policy of armed, nationalistic and border state sovereignty, and to make the (unequal) intergovernmental dimension prevailing on legitimate supranational authorities. We denounce “flexicurity”, the newly coined word that embodies insecurity and precariousness.

We denounce, yes we shall continue to denounce, many other forms of illegality and life destruction.

At the same time, we advance proposals and do we act, exercising participatory democracy, fostering and nurturing civil society networks, and developing human rights teaching and education, cooperating for human development and genuine human security goals. Transnational and cosmopolitan democracy is our flag.

In the era of planetary interdependence, the human rights politica agenda cannot but address the issues relating to world order. But which world order if the human rights paradigm is, should be the compass?

There are two main models of world order that are conflicting today, especially from the end of the cold war: the humancentric democratic-just-positive peace-oriented model, and the statecentric-hierarchic-war-oriented model.

Of course, our human rights agenda refers to the first, based on the International law of human rights, on the centrality of the United Nations, on institutions devoted worldwide to social and economic justice, on intercultural dialogue for the alliance of civilisations, on multidimensional human security.

Consequently and consistently we continue to strive for strengthening and democratising the United Nations: to achieve this strategic purpose we continue to stress that a Global Convention should be organised involving civil society organisations, good-will governments, international and regional institutions, local government authorities, enlightened religious leaders.

We do have many and many proposals. The Peace Table is elucidating and enriching them since the first Assembly of the United Nations Peoples organised in Perugia in 1995, in coincidence with the 50° anniversary of the United Nations. This moment, I would focus especially on some priorities: to develop city diplomacy in order to provide more visibility to the role of local authorities within the UN system, to establish a UN Parliamentary Assembly and ‘interreligious advisory bodies’ at the UN and in the most important international organisastions, to develop the NGOs consultative status up to including formal NGOs “advisory acts”, to establish autonomous national and regional ‘civil peace corps’, to strengthen the ‘civil component’ of peace operations (hopefully including the Ombudsman) in the framework of human security under the authority of a democratised United Nations.

Somebody would wonder whether we have a real power to actually pursue those goals.

I do not hesitate to say that we do have legitimacy to build up such political agenda and we do have power to inject it into decision-making processes at international, national and local level. The International law of human rights is the main resource of our global civil society democratic power. When we advocate and strive for its effectiveness we fertilise the ground for implementing the political agenda.

by Antonio Papisca

Director, Interdepartmental Centre on Human Rights and the Rights of Peoples, University of Padua; Chairholder, UNESCO Chair of Human Rights, Democracy and Peace.